Andre Malraux said, ‘You are not what you show; you are what you hide.’ This is a blog for magicians who regard the art of magic, and how its history is still an important element of that art.” —Jim

JANUARY 2024

THE DOUG HENNING MAGIC THAT YOU DIDN’T SEE

I’m going to take advantage of some unusual video records to discuss some of the magic of Doug Henning which is forgotten today. ln his last two touring shows, there was a number of original pieces developed and built, but they weren’t (generally) recorded on television shows, so there’s not a good record of these effects. They’re the Doug Henning illusions that you may have been lucky to see once—but they’ve been ignored since the mid-1980s.

Doug’s Tunnel Illusion—which always deserved a better name—was very much a creation of Doug Henning himself. As we planned the national tour for 1984, Doug described his idea for a sort of Palanquin Illusion, designed around a square framework. A square tube could be inserted inside of it, which quickly and efficiently created the “magic” for the sequence.

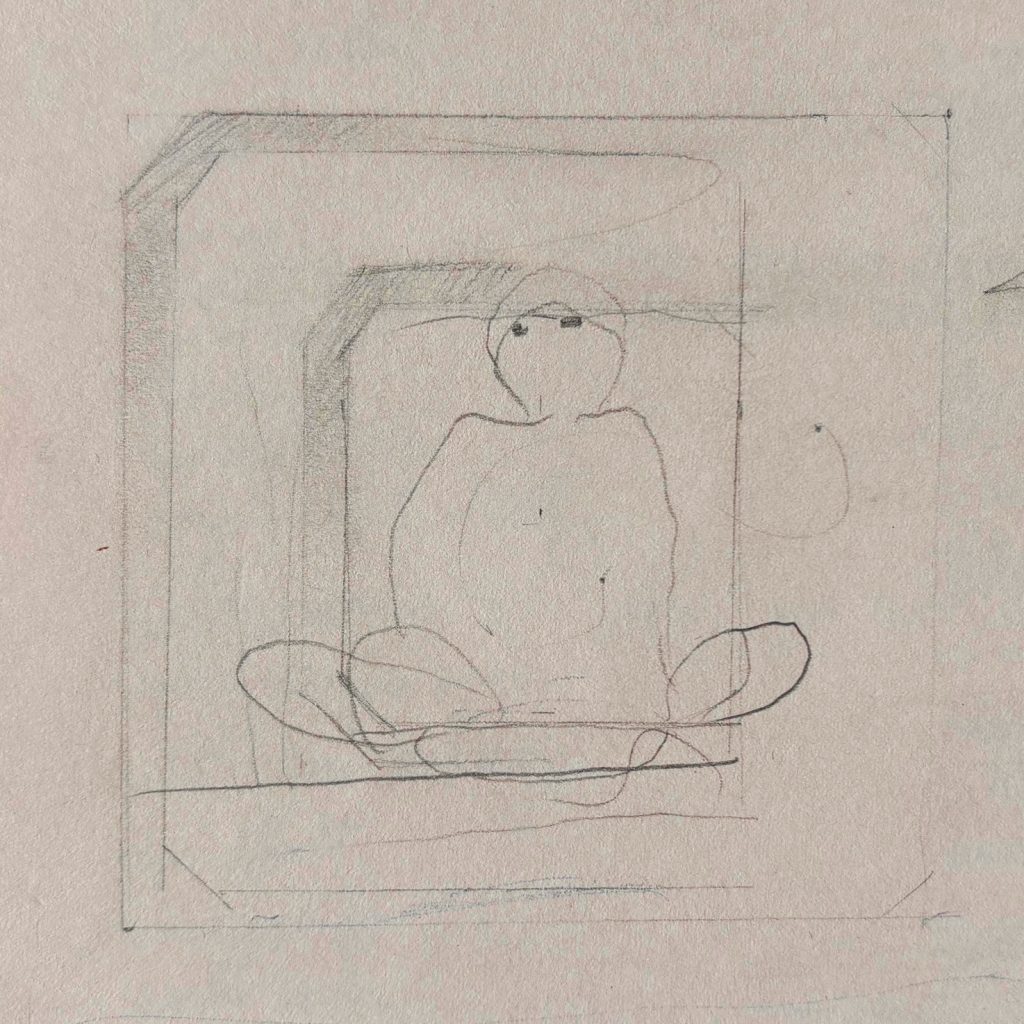

It was not an easy illusion to develop. I was quite sure that Doug’s basic idea wouldn’t work, and we’d have to alter the method to get what he wanted. For one meeting, with John Gaughan, I sketched out the basic proportions in a notebook. Because of the use of the tube, we wouldn’t be able to use the expected illusion “cheats” and deceptions inside the frame. Because the entire illusion was scaled to the human form (in several important dimensions), we were trapped with a set of proportions. I showed the sketch to Doug to explain how the illusion was giving us problems. Doug picked up my pencil, slid my notebook over, and quickly drew in a few looping lines, saying, “See, that’s where she goes. It’ll work just fine.” In fact, his quick sketch wasn’t right proportionally, and he had to adjust the head of the figure, which he did by laughing and drawing in two eyes. Another quick line indicated where he wanted the table. “Johnny will make this deceptive, the way he always does. That’s just how want I want it to be.”

Here’s that drawing. I still have it.

As Doug slid the notebook back to me (note to self: don’t ever draw in anyone else’s notebook, unless you’re invited!) I was convinced that his Tunnel idea would be nothing but trouble and his quick little scribbles wouldn’t solve our problem. But I was wrong. His self-assurance was inspiring, and the illusion work just fine. And most important of all, John Gaughan would really find all the tricks to make it deceptive, the way he always did.

We actually worked extra hard on that illusion, to correct the panels and cheats inside the frame, to correct the dimensions and make it all practical. But John outdid himself. I’ve always considered this prop to be one of his most miraculous achievements, because he had to find completely new solutions to make it work. This was the first prop with a number of important design elements which, in subsequent years, were incorporated into other popular illusions. Those ideas were proven in Doug’s Tunnel.

It was a truly beautiful prop in the best sense of the word. Oh, I know. Other John Gaughan props have polished plexiglas, or bright brass, warm woodgrain or Art Deco curves. Yes, they’re “beautiful” in the conventional sense. But this prop is truly beautiful in its efficiency and design. It does exactly what it has to do. It tells a story. It uses color and highlights do the job, without calling undue attention to itself. Every element, every decision, every dimension, is a work of magic. Notice how the frame is bright and functional, but it’s all subservient to the tunnel. The bright, flashy tunnel is only there for just a few seconds, but it is the focus of the narrative.

Now, just watch the illusion. This is from Doug’s Broadway show in 1984 (and was videotaped from a stage box). When the prop rolls onstage, the actual illusion is just about a minute long, start to finish!

One more thing. It’s not uncommon for an illusion to be tweaked and altered during the process of developing it. Very often, the presentation gets tweaked as well. There might be changes in the pace, in the sequence or the timing. The choreographer might have to add some time, or remove a few steps to accommodate a mechanical necessity.

Doug’s Tunnel—and there’s barely 60 seconds of it—is exactly the way Doug described it to us on that first afternoon at his house. All the beats, all the visual climaxes are right there, exactly in the places that Doug described them. I can tell you, that doesn’t happen very often.