“Andre Malraux said, ‘You are not what you show; you are what you hide.’ This is a blog for magicians who regard the art of magic, and how its history is still an important element of that art.” —Jim

MAY 2022

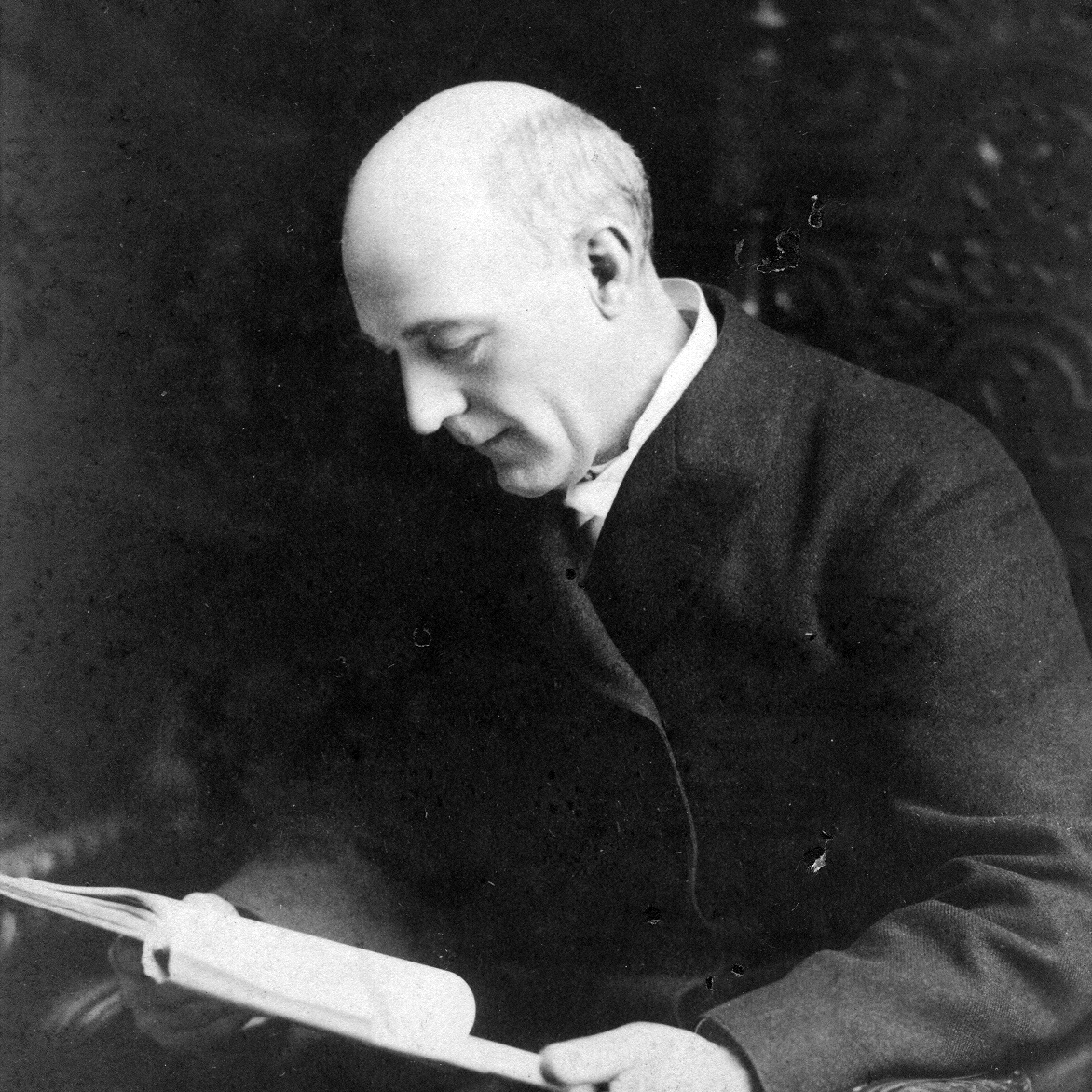

I recently received an e-mail from a reader who was curious about Harry Kellar. Whenever Kellar appeared in my books, he found that he enjoyed his character: Kellar’s blustery, foolish temper and his fulsome apologies, his Horatio Alger-style of diligent, tough business, and his sincere approach to his magic. As he wrote to me, “I adore Kellar and any chance of you mentioning him in any work of yours, I consider a special treat.” For example, he asked me if Kellar really called Thurston “Thursty” when they were offstage. And yes, according to Thurston, he did. Those “slap on the back” mannerisms somehow fit the old fellow perfectly.

I think you’ll enjoy watching a few minutes of Kellar, which we presented at the Magic Castle in May 2016. A friend took a video from the back row of the theater.

Here’s the story behind this video. The act had been assembled for the Los Angeles Conference on Magic History. This video includes my introduction. Kellar was expertly, artistically portrayed by Nicholas Night, who of course had an accomplished career as an modern illusionist. During NIck’s performing days, he never did anything as old fashioned as Kellar’s material, but he had a brilliant, natural way of working with these early 20th century props. He certainly brought a fascinating sincerity to Kellar. Kinga Night assisted as Mrs. Kellar. Robert Ramirez was the other assistant, and provided the music. The apparatus for the act was provided by John Gaughan and William Kennedy.

The tricks are actually what you would have seen Kellar performing. Kellar’s Flower Growth was a specialty that he performed throughout his career; it had been originated by Stodare, and then recommended to young Kellar by his mentor, the Fakir of Ava. Kellar’s method was detailed in the book Elliott’s Last Legacy. The Coffee Trick was another popular favorite, and the presentation is derived from an account of Kellar’s patter. The Queen of the Roses, as seen here, is not quite a Kellar illusion, but it’s close. It was invented by Guy Jarrett, who was inspired by Kellar’s Spirit Cabinet, creating a completely new deception decades after Kellar’s retirement. Although Jarrett never produced it for Kellar, we thought that his incredible invention, lost for many years, should be reconnected with Kellar’s magic.

In 1912, Kellar wrote an article on magic for his friend, the author Fulton Oursler; Oursler later contributed it to the introduction of the American edition of Illustrated Magic. It’s a great, sometimes puzzling mix of high-flown philosophy and old-fashioned, hard-nosed practicality—it’s a lot like Kellar himself. Many of the sentiments would now strike magicians as obsolete, yet it’s hard to argue with his intentions. Above all else, he valued leaving the audience completely and utterly fooled. Even his successor, Thurston (“Thursty”) found this notion slightly out of date, but we know how Kellar fussed endlessly over his tricks to make them perfect novelties and perfect mysteries. When magicians today carry on about how new tricks aren’t necessary, since audiences can’t tell a new trick from an old one (an argument that has been foolishly made, over and over again), I think about Kellar and his inordinate amount of work and skullduggery to bring new magic to his audiences, season after season. Here’s a sample of Kellar’s essay, concluding with his three rules for magicians.

KELLAR’S SUGGESTIONS…

Your art can never arrive at the perfection of art until your handling of the illusion produces a thrill of genuine surprise in all who behold it. That is the end and the aim of the entertainment.

Nor must the magician overlook that in the setting of the stage and every detail of costume, lighting, scenic arrangement or properties, and all accessories must provide a picture and supply an atmosphere which is conducive to mystery.

When I am asked to what I attribute my success in the profession, I say, chiefly two things: Incessant and indefatigable practice of the fundamental passes, tricks and feats which are the basis of all magic; and my own original development of extraordinary combinations of these simple formulae, with an elaborate overlay of artistic trappings.

You can never interest the modern public unless you are continually giving them something new. But if you do succeed each season in producing some new illusion which seems novel, no matter how old its solution may be, your fame as an entertainer is secure.

First: Practice constantly new sleights, novel devices and invent new combinations of old feats. You must have something always new wherewith to dazzle.

Second: Make your work artistic by clothing each illusions with all the glamour and shadows of fairyland, and the suggestions of incantations and supernatural powers in order to prepare the observer’s mind for a mystery, though there be no mystery.

This: Study your spectators and seek to put them under your control even as the mesmerist does his subjects, so that their minds should be receptive to theories of the occult, and their eyes be shut to the obviously simple explanations of your prestidigitation.

Finally, I need not say that the end of all magic is to feed with mystery the human mind, which dearly loves mystery.