“Andre Malraux said, ‘You are not what you show; you are what you hide.’ This is a blog for magicians who regard the art of magic, and how its history is still an important element of that art.” —Jim

JULY 2022

THE WORD IS “ABSTRUSE”

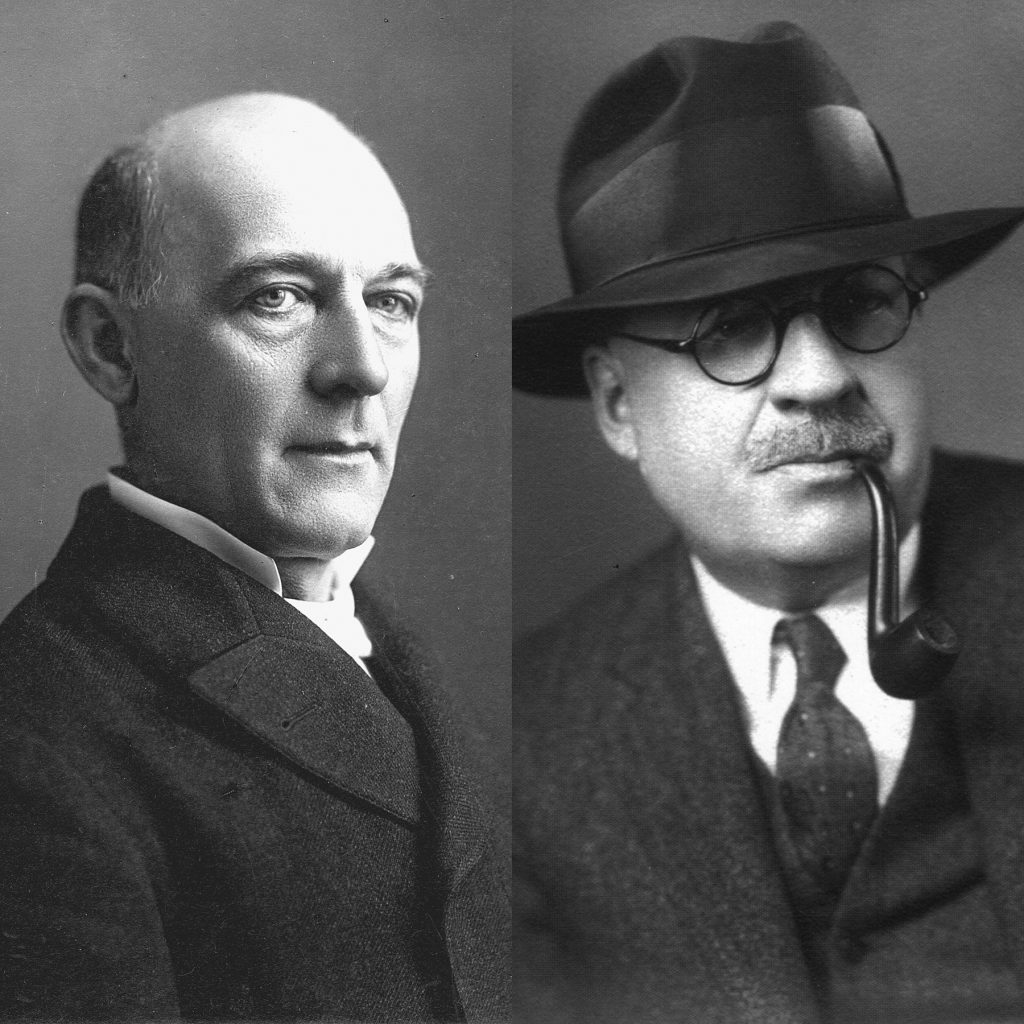

Harry Kellar—who early in the 20th century was America’s greatest magician—was temperamental and impulsive. John Northern Hilliard—who, at the same time was a lowly newspaper reporter and reviewer in Rochester, New York—was a particularly proud and fastidious writer. He was also a talented amateur magician.

That was part of the problem. Hilliard was critical of Kellar for his lack of sleight of hand skills. Years earlier, Herrmann had been deft and artistic onstage, flexing his fingers as he indulged his European bonhomie. Instead, Kellar’s personality was solid, avuncular, and coarsely (to many, refreshingly) honest. Rather than play the part of Mephistopheles, Kellar just conducted mephistophelian marvels. When Kellar hired Paul Valadon to join his show, Hilliard celebrated by praising the performance, complimenting the inclusion of Valadon’s sleight of hand, and admiring Kellar as a “magical entertainer.”

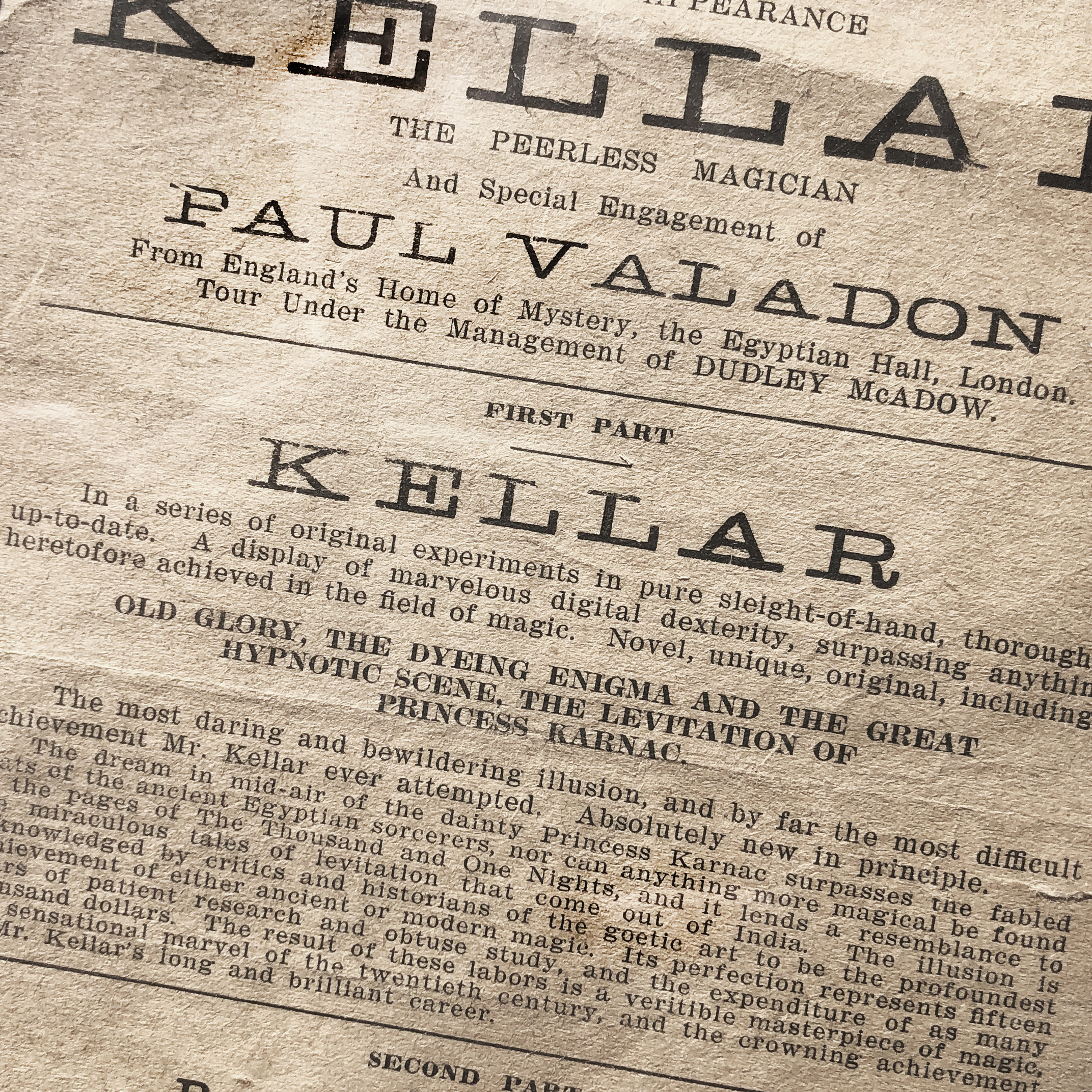

Kellar’s honest approach is still apparent in the scraps of publicity and patter that have come down to us. Here was his patter for his spectacular Levitation of Princess Karnac.

Some six years ago, my company and I made a trip to India, the cradle and land of magic, where magic is not written in books but is handed down from father to son by word of mouth. While on this tour, it was our good fortune to witness a performance of the Great Ali Ben Bey. We saw him lay a native Hindu lad, seven or eight years of age, upon the sand at his feet. After Hindu incantations, of which neither I nor my company understood a single word, the boy rose into the air to a height of possibly five or six feet, defying all laws of gravitation, there being no visible means of support.

He then passed for our inspection a hoop made from the bark of some native tree of India. The hoop was wrapped with leather thongs which resembled our own American pigskin, but most likely was the skin of some wild animal. After we were satisfied it was without break or split, it was passed completely over the floating body, not once but twice, proving the absence of all means of support known to mechanical science.

After this most mystifying demonstration of a magic new to both my company and me, I went out to the Hindu magician with an offer which, if he accepted at that time, I would have been unable to pay.

He, being a Hindu and reared within the circle of magic and mystery, refused to part with his wonderful secret. I, being an American and determined as all Americans are, followed this Hindu friend. Three weeks later I found him on the banks of the Ganges River and discovered the secret of this greatest of all mysteries. I now present it to you as witnessed in India six years ago. Ladies and Gentlemen, “The Levitation of Princess Karnac” for your approval. The Princess Karnac….

Kellar was unable to weave a complete fairy tale without boasting like a typical American entrepreneur, discussing is finances or hinting at how he purloined the secret. This approach was also used in the brief paragraph in his program that announced the new levitation:

Absolutely new in principle, it is the outcome of experiments extending over a number of years, and in which more than ten thousand dollars have been expended. Experts who have witnessed the mystery declare it to be the most inexplicable mystery that has ever come within their expertise.

Even Kellar must have realized that the schoolboys who attended his show didn’t want their dreams of magic translated into dollar signs, so he recruited Hilliard, his new friend, to write a poetic program description of the levitation. He knew that Hilliard could use some of those two-dollar words and make it sound fancy, so he offered him $50 for the job, the story goes. That’s a fair bit of money; more than $1500 at today’s rate. Hilliard knew exactly how write a paragraph that would enchant the schoolboys who took their seats and carefully studied the magician’s program as if it were real literature. So Hilliard offered:

The most daring and bewildering illusion, and by far the most difficult achievement Mr. Kellar has ever attempted. Absolutely new in principle. The dream in mid air of the dainty Princess Karnac surpasses the fabled feats of the ancient Egyptian sorcerers, nor can anything more magical be found in the pages of The Thousand and One Nights, and it lends a resemblance to the miraculous tales of levitation that come out of India. the illusion is acknowledged by critics and historians of the goetic art to be the profoundest achievement of either ancient or modern magic. Its perfection represents fifteen years of patient research and abstruse study, and the expenditure of many thousand dollars. The result of these labors is a veritable masterpiece of magic, the sensational marvel of the twentieth century, and the crowning achievement of Mr. Kellar’s long and brilliant career.

I’ve written about this before, but let me pause here to admire Hilliard’s prose. That paragraph is a masterpiece. Much of it reads like common-sense, a newspaperman’s facts, with Kellar’s hardboiled boasts and superlatives that were so fashionable in American culture. Yet is is still woven with sheer fantasy. That one phrase, “and it lends a resemblance to the miraculous tales of levitation that come out of India” is spectacularly wobbly in a purely intriguing way. Indicative of Hilliard’s genius, the words are stacked to create and incredible tower of mysticism and skepticism, and then Hilliard seems to perform a pirouette on top. He also includes some great two-dollar words: goetic, abstruse, veritable. By starting with the “dream in mid air of the dainty Princess Karnac” and concluding with “the sensational marvel of the twentieth century,” he was able to turn Kellar into an Edison of real magic. Mysticism became a commodity.

Kellar liked it, but as a businessman he felt that, for fifty dollars, it should be longer. Maybe a page long. Hilliard was adamant; he was a skillful wordsmith and he realized that its brevity was part of its appeal. Kellar agreed that he would pay him only $25 for this single paragraph, and Hilliard fumed at being shortchanged.

Hilliard had the last laugh. Somehow, he managed to tweak the final draft. Instead of “abstruse” (“hard to understand, profound”) he substituted the word “obtuse” (“stupid, slow at understanding”). That is, he wrote that the trick was the result of fifteen years of stupid study.

Hilliard probably realized that Kellar didn’t have anyone around him who would recognize the error and correct it, and he was right. For over a year, Kellar’s program boasted of his “obtuse” study. It’s a reminder of that excellent advice attributed to Mark Twain: “Never pick a fight with a man who buys ink by the barrel.”

Some time after this, Hilliard had another reason to feel double-crossed. It became apparent to American magicians that the levitation was not so much Kellar’s invention so much as a theft from John Nevil Maskelyne, who had introduced the original version of this effect at Egyptian Hall in London. Paul Valadon, a former Maskelyne magician, must have provided some of the technical details when he came to America to join Kellar. Kellar diligently turned Maskelyne’s invention into a practical illusion that could be put on the road. Hilliard had been deliberately deceived about the trick. Still, if he would have just listened carefully to the patter, he would have found Kellar’s blunt honesty, all wrapped up in that fantasy about India:

(When he) refused to part with his wonderful secret. I, being an American (was) determined as all Americans are… I found him… and discovered the secret… I now present it to you.

Just a couple of years later the Kellar show was purchased by Howard Thurston and he presented the spectacular levitation. Thurston’s good friend John Northern Hilliard provided a new edit of the magical paragraph, tailored to Thurston and politely acknowledging Kellar’s introduction of the feat. And for Thurston, Hilliard switched the word back to “abstruse.”

In the next blog, more on the levitation. We’ll get to hear music that described Princess Karnac’s mystery in Thurston’s show. This brilliant, dream-like example of stage magic was fondly remembered by the audiences that fell under Thurston’s spell. One Thurston fan long sought this music, but it actually went missing for over 75 years… Soon, you’ll hear it.