“Andre Malraux said, ‘You are not what you show; you are what you hide.’ This is a blog for magicians who regard the art of magic, and how its history is still an important element of that art.” —Jim

SEPTEMBER 2022

THE MAGICIAN, THE BANANA STALK, AND THE NAZI

In the late 1920s, a magician and comedian became a roaring success on stage. George Lovejoy Rockwell presented his act wearing horned rimmed glasses, a black tailcoat, striped trousers, a mortar board and a stethoscope. He puffed on a long black cigar. When he was enthusiastically introduced, “Ladies and Gentlemen, Doc Rockwell!” he dashed onto the stage completing the introduction by croaking, “Quack, quack, quack!” and then, by all accounts, held the audience in fits of hysteria during his act. He even reappeared throughout the show, turning up in the theater box, continuing his monologues, commenting on the show, dropping his false teeth and then reclaiming them by pulling on a string that had been tied to the dentures. “They’re not mine,” he explained. “I’m just breaking them in for a friend.”

Doc Rockwell was a nut comedian, in the Marx Brothers, Joe Cook, Clark and McCullough model. He rattled through his patter a mile-a-minute, providing improbable scientific lectures filled with unexpected malaprops and puns. Most of his material centered around medical theories or outrageous health advice.

Rockwell started as a magician, but he insisted that he bungled his tricks so badly, losing the card in the deck or breaking the thread, that he was forced to come up with comic solutions to pull himself through the act. When a red silk handkerchief refused to disappear, he explained to the audience:

It just goes to show you that you cannot trust a stagehand. I had a black silk thread with one end tied to the handkerchief and the other end tied to the cat’s tail backstage. In front of the cat was a mouse in a wire cage. At the appointed signal, the stagehand was to let the mouse out of the trap and when the cat chased the mouse it would go so fast that the thread would pull the handkerchief out of the glass and cause it to vanish offstage. I paid the stagehand two dollars in advance to help me, but he spent the two dollars on liquor and is sound asleep.

You can anticipate what happened; he soon abandoned the magic altogether and focused on the insane explanations. His own interest in natural foods and remedies led him to parody America’s obsession with health theories. An early act was called “How to Live to be 150,” and he became a star in the George White Scandals, and later the Greenwich Village Follies, the sophisticated revue show that played on Broadway at the Wintergarden Theater. He toured on Keith vaudeville, and appeared in Billy Rose’s Broadway review, The Seven Lively Arts, in 1944.

His most famous bit was to enter brandishing a banana stalk, a 4-foot branch that supported multiple bunches of bananas, and use it to illustrate the human skeletal system.

Let us consider the skeleton… This is merely a man with his insides out, and his outsides off…. The bony framework of the body consists of 200 assorted bones, nuts, and bolts with this structure running up and down the back known as the spinal column, or backbone. Some people have more of this than others…. Up here in the attic, people keep that filled with all sorts of junk. Then comes the dining room, then the sitting room. In other words, your head sits on one end of the spinal cord, and you sit on the other…. In considering the skeleton, we start at the top, up here, and we have the skull bone. Then the collar bone, the wishbone, the soup bone, trombone, and so on down to the outboard motor…. If the eighth vertebrae gets pushed out of place, all of your children will be born with straw hats and woolen mittens. When the thirteenth vertebrae is dislocated, it leads to the development of boils, carbuncles and Chevrolets. The Chevrolets will probably give you more rear end trouble.

He later used a tangle of wire coat hangers to lecture on the human ribs, and his finale was to play the “William Tell Overture” on a tin whistle; every time it was about to conclude and the audience was poised to applaud, he’d start all over again.

Rockwell continued to associate with magicians, suggesting tricks or presentations. He thought that it was a disadvantage to bill an act as magic; it would be more interesting to call it “Psychology Applied,” or “A Study in Applied Misdirection:” something that intrigued the audience and teased them into watching.

He wrote for Fred Allen, and occasionally appeared with him on the radio. He made a brief, unbilled appearance in the movie “The Singing Marine.” For many years he published his gags and jokes in his newsletter, Ye Olde Mustard Plaster, which has been credited as a forerunner to MAD Magazine, and was a columnist for Downeast Magazine. As old Doc was fond of saying:

Let joy be unrefined!

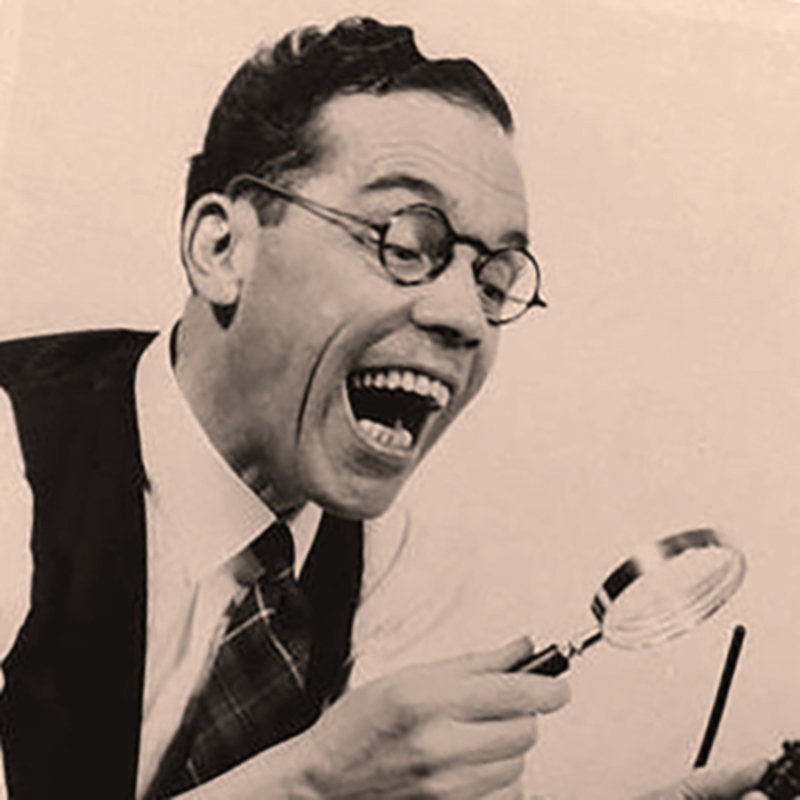

Those photos show Doc Rockwell in Hollywood, and his son at party headquarters… which brings us a very weird twist in the story.

George Lincoln Rockwell, Doc’s son, was born in 1918, when his father and mother were both struggling vaudevillians. When he was just six years old his parents divorced and he bounced between them. Doc Rockwell moved to Boothbay Harbor, Maine. Sid Lorraine recalled one of Rockwell’s weird gags for his fellow magicians. He’d talk about his young son, explaining that he didn’t think he’d go into show business. Pulling a photo from his wallet, he’d show the picture of a small, emaciated native boy from a far-away country, from some news source. “He wasn’t feeling too good when I took this picture. I don’t think he’ll amount to much,” he’d blithely say. His friends laughed, but his gag was strangely prophetic, suggesting the careless relationship between father and son.

George Lincoln was enrolled in Brown University, studying philosophy, but he dropped out and joined the Navy, becoming a fighter pilot during World War II. Despite being named for a great American hero, the young man was strangely drawn to the extreme politics of the Nazi party, accepting Hitler as the “white savior.”

His son became a personal tragedy for the old vaudevillian, Doc Rockwell. Sid Lorraine remembered that Doc Rockwell denounced his son’s politics at the beginning of the young man’s career, but then stopped talking about it, out of frustration. Soon, the young Rockwell had moved beyond “the farthest fringe of the right wing,” and became a devoted Nazi. George Lincoln’s devotion to the Nazi movement remains a puzzle.

Young Rockwell—the famously awful Rockwell—attended marches, gave speeches, and decried the Civil Rights movement, black citizens, and Judiasm. He also denied that the Holocaust took place. As he insisted:

Revolution is a spectator sport. At the end they will choose side with the team that is winning.

In 1959 he founded the American Nazi party and was its first leader. Rockwell’s taste for boundless, hateful speech earned him notorious celebrity. In 1967, he was shot and killed by a disgruntled former member of the party who had been rejected by George Lincoln Rockwell for Marxist views. The killing made headlines.

Although Doc continued to be loquacious on many subjects, his friends knew to politely never mention his son. The comedian seems to have made only one brief statement about his son’s death: “I am not surprised at all. I’ve expected it for quite some time.” Decades earlier, he’d convulsed vaudeville audiences by pointing out how, “up here in the attic,” people collected “all sorts of junk.” By 1967, he’d long been retired from show business, and managed a ramshackle inn in Boothbay Harbor. He caught lobsters, wrote letters, and returned to an old skill, sign painting, to amuse himself. His letterhead read, “Rockwell Signs, Made While you Wait, and Wait and Wait!”

Doc Rockwell—the famously funny Rockwell—died in 1978.