“Andre Malraux said, ‘You are not what you show; you are what you hide.’ This is a blog for magicians who regard the art of magic, and how its history is still an important element of that art.” —Jim

SEPTEMBER 2022

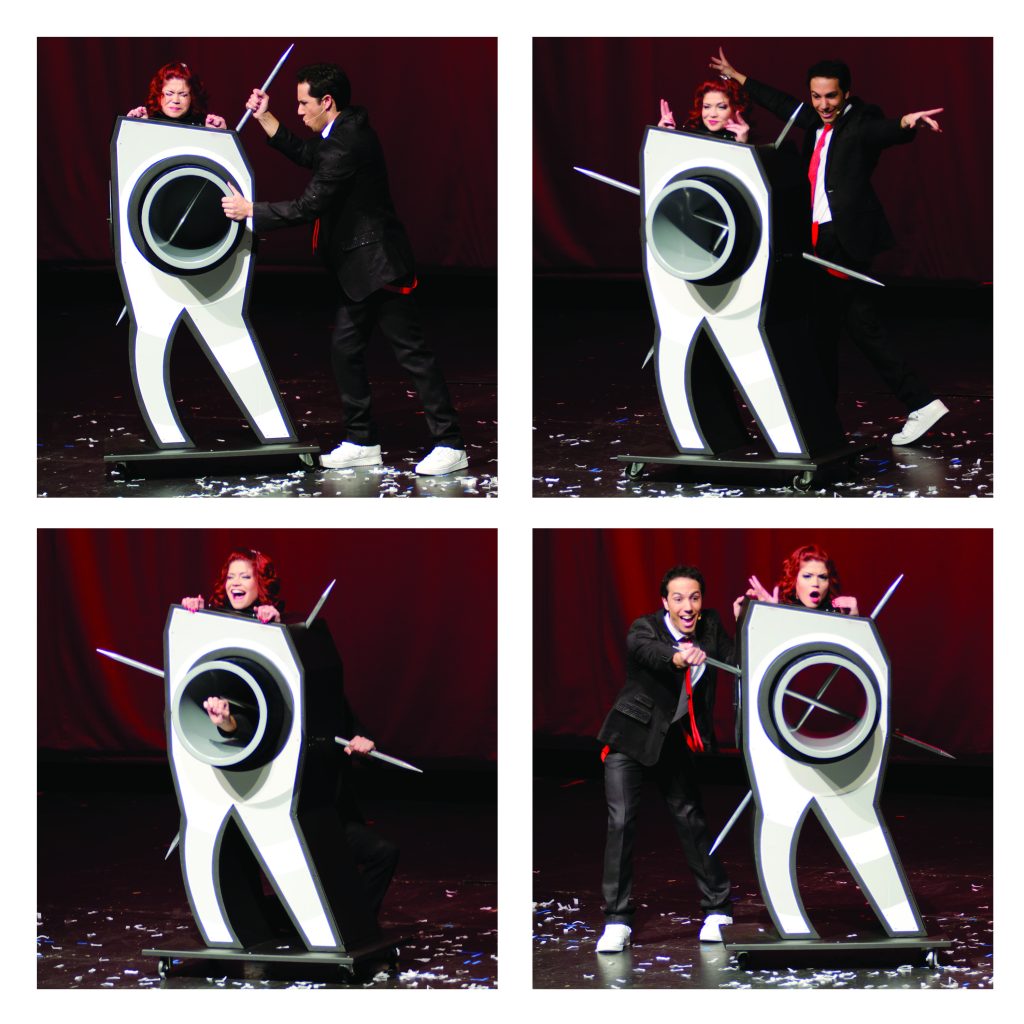

30 SECONDS OF AN EVO-LUSION!

I started work on the illusion (that became Heartless) some time in 2010. It was inspired by conversations with Alan Wakeling, many years before, and by recent experiments involving several props working with Willie Kennedy. When Alex Ramon finished his two year run with Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus, we discussed various ideas for effects for his own show, and one of those was Heartless. It was an experiment for Alex, too. He had spent the previous seasons prancing across arena floors like Madison Square Garden or the Staples Center, performing the Vanishing Elephant, a super-gigantic Wheel of Doom, a clown cut in half, and a levitation of three parents from the audience (each one conducted by their kid, dressed as a wizard). The circus doesn’t do anything half-way, nor does it bother with economy-sized elements. So Heartless was, at that moment, a mere illusion for Alex, and a chance for him to redesign his shows to suit a merely stage-sized performance.

It was produced in 2011, in a gradual process of designs and mock-ups. I’ve found that, reduced to 30 seconds, it all looks pretty easy, doesn’t it? Certainly, this is the most deceptive, most entertaining way to watch it all come together!

And it looks easy, doesn’t it? A few drawings, a few pieces of metal. Maybe it wasn’t easy, but it certainly was fun, because of the people involved and the sort of unified understanding of what we were trying to achieve. To me it represented a chance to do some things in a different way, but looking back on it now, the wonderful thing about the experience is that everything was different. It was about the prop. It was not about trying to make it look like a cardboard box, or a chair, or any of those century-old affectations that we read about in magic books; the magician mumbling or bowing and scraping to the audience, in order to apologize everything away. This was about using the prop—the prop containing, becoming, representing the person and, as Alex performed it, as the third dance partner. Everything worked together, and as the prop and the illusion became the same thing, it was a chance for everything to be different. Or, as David Devant wrote:

Perhaps the most beautiful thing in the universe is harmony, or unity. A perfect work of art is one harmonious whole. the perfect result cannot be obtained in any haphazard method; it must all be arranged. Once complete, it cannot be broken in any part without destroying the whole structure; one part must support another and must dovetail in so perfectly that it is impossible to tell them apart. The plan must be perfectly conceived and carried out.

When the prop was finished, we changed plans again. I’d been playing with colors and patterns, and it became obvious that a monochrome design would be just right—the whole thing became about the performers and the sculptural, surrogate body that formed the apparatus. Black, white, gray, as if it’s all about shapes and shadows. Every visual touch reinforced that.

Devant was right. Heartless began to tell us what was right, and tell us how to make the elements work perfectly. The performance was different, too. Alex looked at the illusion as a challenge and an artistic endeavor at the same time. The idea of a brand new illusion wasn’t daunting for him: no classic performance to copy, to videotaped magic special to study. He developed a routine, premiered it in 2011, and performed it at the Magic Castle in November of that year, in a show called “The Old and the New Magic” which combined some historical illusions with some brand new effects. Since then, Heartless has been a part of Alex’s illusion show.