“Andre Malraux said, ‘You are not what you show; you are what you hide.’ This is a blog for magicians who regard the art of magic, and how its history is still an important element of that art.” —Jim

OCTOBER 2023

MASKELYNE’S FAMOUS MAGIC PLAY, EXAMINED

Over the last few years, I was engaged in a project to re-stage John Nevil Maskelyne’s famous magic play, Will, the Witch, and the Watchman for a West End production. The directors toiled mightily. They wrote and rewrote, determined to update the script and change a number of the illusions. They took on a fascinating challenge. I was asked to execute the illusion designs, as I had rewritten, restaged and produced the play in 1997 for The Los Angeles Conference on Magic History. But despite everyone’s best efforts, this famous magic production proved elusive. It just couldn’t fit the directors’ ambitious plans, and it was abandoned before a single performance. It remained a frustrating “near miss.”

What happened? Since I’ve been asked about it, I can only note the various complications and difficulties. Certainly, the original play was a production of its time, stamped distinctly as a literary and visual representation of popular Victorian stylings. So it’s a good time to take a look at the actual production, and the story behind this famous magical masterpiece, a moment when conjuring seemed to march into the theater and produce a wonderful hybrid of comedy and illusion. This blog (Part One) will explain a little bit about the history of the play, including a few astonishing pictures related to its history. The next blog (Part Two) will let you watch the 1997 production, the only time that Will, the Witch and the Watchman has been seen by an audience in nearly a century.

It started as a ghost story. In 1865 a dapper young Cheltenham magician, John Nevil Maskelyne, saw the Davenport Brothers, two American Spiritualists, give a demonstration at the genteel spa’s Town Hall. The brothers’ performances were topical and religious sensations. But at that particular show, a bit of drapery happened to fall from a window during the Davenport séance, allowing a brief ray of sunlight.

In a flash, Maskelyne saw a wriggle of motion inside their wooden spirit cabinet. Instead of summoning ghosts to strum guitars or bang on tambourines, the Davenport Brothers had escaped their bonds to produce the ghostly manifestations themselves, and their supposed Spiritualism was merely a confidence game. Together with George Cooke, his performing partner, Maskelyne produced a rival séance—this one presented honestly, as a feat of sheer trickery.

A canny showman, Maskelyne evolved his performance to something less academic and far more fun. The spirit cabinet became a wooden jail cell. He added a cackling old witch, a confused Irish watchman, and a rambunctious monkey. (There was a short-lived fashion for performers in monkey costumes in the Victorian theater.) De-emphasizing the ghosts and gradually dialing up the surprises, Maskelyne and Cooke called their sketch Le Dame et la Gorilla, The Mystic Freaks of Gyges, and finally, Will, the Witch, and the Watchman. (To insiders, it was WWW.) Maskelyne incorporated better jokes, flashier scenery, and his latest optical illusions. In 1873, WWW was ready for its London premiere at the Maskelyne and Cooke theater, Egyptian Hall in Piccadilly.

WWW was a hit. It was revised over the decades, becoming a finely-tuned, perfectly silly warhorse of a production. Maskelyne often played the Witch, wearing a long black cloak and a papier-maché mask. Cooke played the monkey. The Maskelyne family claimed that the play was performed over 11,000 times, which might be possible when you consider that it toured the provinces, was featured across America, and even imported to Australia.

Although other magicians had experimented with sketches, it was WWW that established the perfect mixture of magic and farce. Maskelyne’s magical innovations also made history. In one of his original sequences, the monkey escaped from a locked trunk. It was an idea that, a generation later, made a career for a fledgling American magician named Houdini.

Egyptian Hall became a popular London institution, where regular matinees (“Daily at 3 and 8,” the posters read) were enjoyed by generations of tourists and British children. We might wonder whether the author C.S. Lewis, who would have been treated to a Maskelyne magic show as a boy, was inspired by the memory. Instead of Will, the Witch, and the Watchman, a play centered around a two-doored wardrobe, Lewis later titled his famous fantasy novel, The Lion, the Witch, and the Wardrobe.

Maskelyne unveiled dozens of magical inventions, and more than a few popular plays. Just after the start of the 20th century, Egyptian Hall was razed and the Maskelyne theatre moved to St. George’s Hall on Regent Street, with a new partner, the popular British magician David Devant. Although Maskelyne lavished attention on the play early in his career, by the time of WWI (a very different acronym!) his script had become slow, stale, and magnificently out-of-date. David Devant brought a new style of magic to Music Halls, but Maskelyne stubbornly dug in his heels, insisting that WWW demonstrated how his old magic was still popular. It wasn’t. Wartime audiences, desperately seeking diversions, had little taste for the wheezy Victorian puns. One of Maskelyne’s last appearances on stage was as the Witch in London, just weeks before his death in 1917.

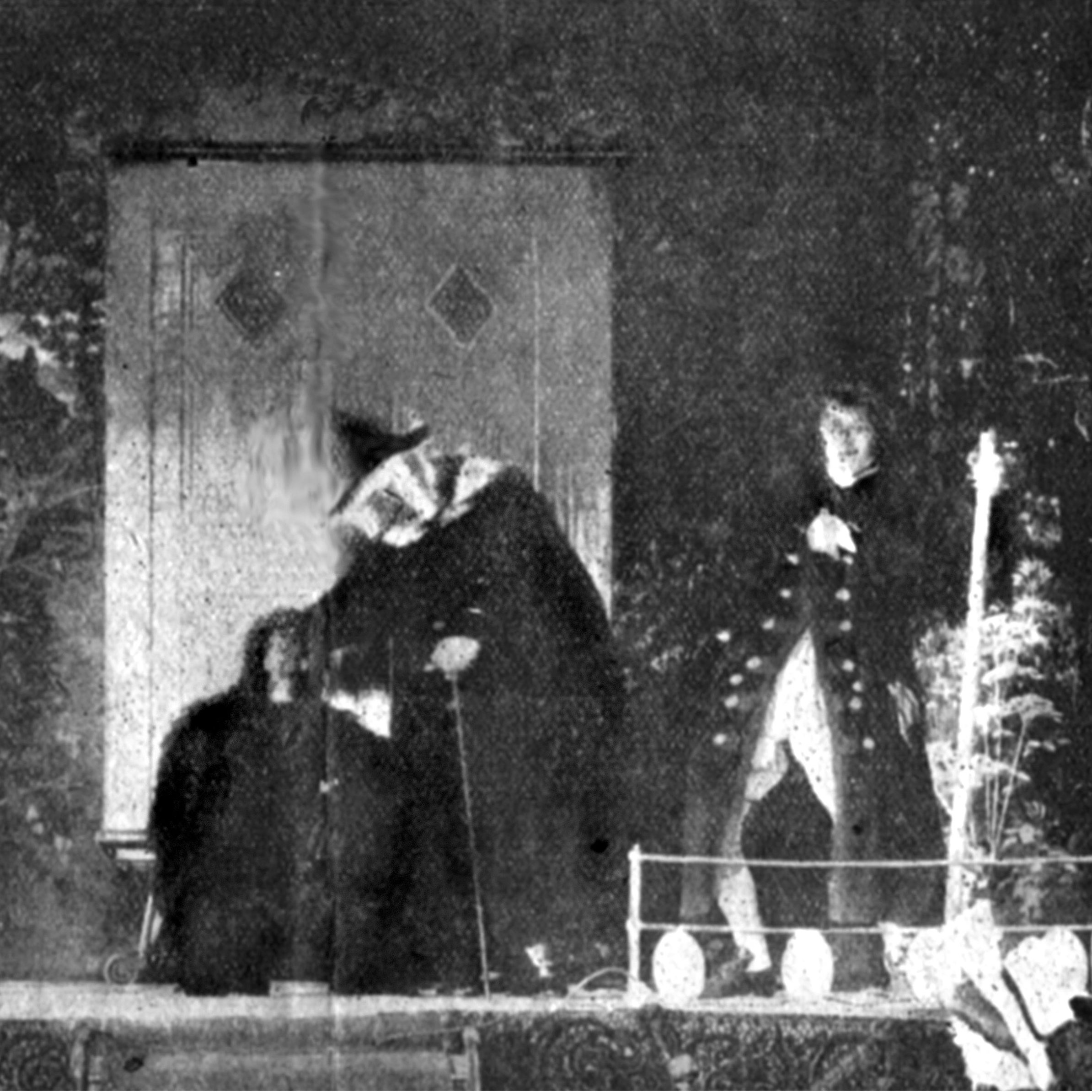

The photo heading this blog page is an extremely rare picture taken of a stage performance inside Egyptian Hall, circa 1895. Onstage is Will, the Witch and the Watchman. If you look at the montage just above this text, you’ll see the full photo. Notice the low “fence” across the front of the stage and the footlights. In front, to the left, is a piano. Onstage, on the far left is a spectator from the audience, seated and watching the action from up close. Maskelyne began the performance by inviting two spectators to examine the apparatus, and then watch the play from onstage. To the right of the man is the famous Maskelyne box trick, a trunk escape, with Dolly leaning against it. The trunk is on its end, with the lid opened. At this time, Dolly appears to be Lillian Morritt, who sometimes played this part when her husband, Charles Morritt, was working with the company. To the right of her is Daddy Growl. Then, in front of the cabinet is the Monkey, crouching, and the Witch; these roles taken by George Cooke and John Nevil Maskelyne themselves. To the right of the Witch is Miles, the comedic star of the show, holding a staff. To the far right is the second spectator, seated onstage. Notice the famous cabinet, the “lock up” or portable jail, behind the Witch and Monkey. You can see the rough dimensions of it, the small windows in the doors, and even see the caster on the front wheel. Behind the cabinet is the “forest” scenery, showing painted foliage.

The lower photo, on the left, shows the monkey inside the famous trunk escape. Again, the round-backed trunk is upright, on its small end, with the lid opened. The center portrait is John Nevil Maskelyne. The colored poster on the right is from the first years of the 20th century, advertising the play on tour, when Maskelyne and Cooke’s productions played the provinces and were managed by David Devant. The image give an idealized, fairy-tale visualization of the play. Notice the Witch, at the left, Daddy Growl and Miles, the watchmen, and the Monkey atop the cabinet, tormenting Miles.

Part Two of this Blog will include the 1997 performance, a rare opportunity to watch the entire play in action.